Losing and Gaining (Calorie Storage and Retrieval)

This is where things really start to get interesting.

What You'll Learn and Why It's So Great

Knowing the truth about gaining and losing will give you control, flexibility and confidence in your ability to lose weight and maintain it. You won't worry so much about "wrong" or "right" foods ... or about getting off track for a meal, or even a day, or a weekend. You'll see how your body already gains and loses (stores and retrieves) calories on a daily basis and how to control it simply by calorie intake. (Yes, nutrition is important but everything ultimately comes down to calories.)

Let's get started...

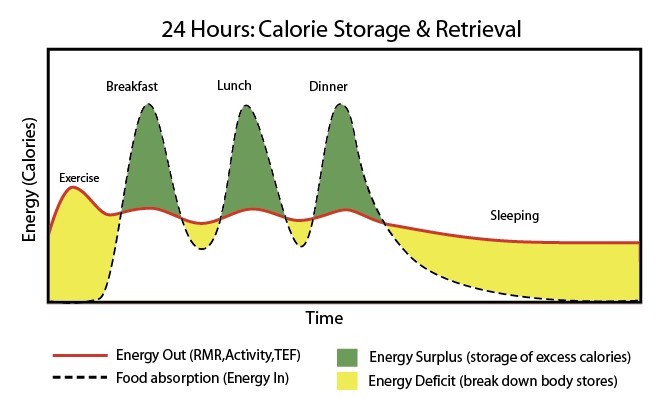

Take a look at this:

Please realize the graph above is very simplified. Digestion and absorption are complex. The curves of the graph depend on how much you eat, when you eat, and what you eat. The spikes and dips may be much less dramatic with foods that take longer to digest and absorb (like whole foods with protein and fiber content), and it's possible you may not go into a calorie deficit between meals. Even so, this graph should be really helpful. We'll look at an example below to make it even more clear.

Note that the red line (Energy Out or Total Energy Expenditure (TEE)) goes up and down slightly throughout the day, depending on your physical activity and food processing (TEF). It's lower and more steady during sleep.

Before going into our example, keep these points in mind:

-

Calorie storage and retrieval in the body occurs on a daily basis

When you eat (especially a larger meal) your body tends to store some calories because it can't use that many calories at once

However, your body can quickly tap into those stored calories when food intake stops

Energy storage and retrieval happen because it is impossible to get the precise amount of energy and nutrients you need at the precise rate your body is burning them, so instead, you digest food and store it for later use. The only way you could avoid storing calories is if you were hooked up to a constant intravenous infusion directly into your veins that delivered calories always equal to your current rate of energy expenditure. Instead, your body is responsible for precisely extracting and using stored energy (incidentally, when that process goes overboard due to faulty insulin signaling, you get too-high blood sugar and lipids).

Example Scenario

Look at the graph again.

Let's assume the following example:

-

Your RMR is 1560 calories; that means your body burns 65 calories per hour

You burn 340 calories during your morning exercise routine (the hump in the red line at the left).

Other than your morning exercise, you get little to no activity

So your total energy expenditure (TEE) is roughly 1900 calories over 24 hours.

We'll refer to those numbers in our discussion below.

Now, let's say you eat 3 meals, each containing 633 calories, for a total of 1900 calories.

For simplicity we'll say it takes a total of 5 hours for the food in one meal to be absorbed; that means every hour 127 calories is available for energy. Yet during that time your body is expending only 65 calories per hour. That means you are storing 62 calories per hour while you are digesting and absorbing food -- an energy surplus, also called the "fed" state. In this example, the fed state lasts 15 hours (3 meals x 5 hours), so you end up storing a total of 930 calories (15 hrs x 62 calories) in body tissues.

However, during the other 9 hours of the day you are in an "energy deficit" -- there's no incoming food available so your body taps into the energy it stored earlier in the day. Over those 9 hours, your metabolism burns off 585 calories (9 hours x 65). Of course this deficit continues during sleep -- if you eat your last meal at 8pm and it takes 5 hours for it to be absorbed, then around 1AM, your body turns to stored fuel that lasts until you eat your next meal. You're literally burning calories for half of the night.

Add 340 calories burned during your morning exercise to the 585 burned during the night, and you're now in energy balance. That means no net storage of calories. If it stays that way over time, you will maintain your weight.

In this example, you should be able to see that:

-

If you were to eat the same and not exercise, you would store 340 calories per day... so you'd gain weight over time

If you were to reduce your meals to 500 calories each, and keep exercise the same, you'd be in an energy deficit by 400 total calories per day... so you'd lose weight over time

If you were to not eat breakfast, and keep your other meals and exercise the same, you'd be in an energy deficit by 633 calories per day... and you'd lose weight over time

You could eat one monster meal of 1900 calories, and if you fasted the rest of the day, you're in energy balance and would not gain weight

You should also see you can't cheat the system: whether you eat 10 meals a day or 1 meal, eat late at night, skip breakfast, exercise at night or in the morning, what determines weight gain or loss is how calories in equates to calories out over a period of time ... whether you are talking about a day, a week, or a month. If you have an energy surplus one meal, one day, or one week, as long as you create an equal energy deficit some point later, it evens out. If it doesn't even out, you gain or lose weight.

You should now have a clear picture of the cycle of calorie storage and retrieval compared to the rather steady state of your body's metabolism.

Little Known Facts About Storage of Excess Calories

You have probably assumed all along that we are only talking about FAT storage and retrieval. Actually, the body can store excess incoming food in three ways, not just as fat tissue.

Here are the 3 main ways the body stores excess calories in the body:

-

Fat tissue

Glycogen (carbohydrate storage)

Protein (as muscle)

Fuel Preference & Storage Priority

Your body is constantly in need of a regular, steady stream of calories.

For the most part, all tissues in the body can use both glucose (carbs) and fatty acids (fat) for fuel. There are a few exceptions or certain conditions (like ketosis we discuss elsewhere) but the important point is to realize that both fat and carbs are easily and readily used by the body for fuel. In fact, the body is constantly burning BOTH carbs and fat, depending on your activity level and availability of each nutrient.

Glucose (carbohydrate) is the body's preferred energy source. We don't know exactly why, because the body can obtain energy without it (e.g., ketosis). What we do know is this:

-

Glucose is the default fuel source for the brain.

Glucose stored in muscle is required for high-intensity activity.

The body can only store a very limited amount of glucose (roughly 1600 calories, as glycogen)... in contrast with unlimited fat storage capacity.

It is very costly energy-wise to try to transform carbohydrates into something else (e.g., fat).

If the body does not need incoming carbs for immediate energy requirement, it stores it in the liver and the muscles as glycogen. Glycogen is a compound consisting of water and glucose (not fat!). Note that glycogen storage is not unhealthy -- it's a good thing. It provides fuel for working muscles. And your body liver glycogen is used to supply a steady amount of glucose to the brain. So over the course of a day, those glycogen stores are being used to supply energy between meals.

After topping off glycogen stores, if there are still carb calories remaining, the body increases the metabolism to try to burn off excess carbs (this effect can vary quite a bit by individual).

Body fat storage, on the other hand, is unlimited, and it is a concentrated source of energy. Every gram of fat contains 9 calories -- more than twice as dense as carbohydrate or protein. So the body is very efficient at storing fat. Dietary fat is stored either in fat cells or in muscles as IMTG (intra-muscular triglyceride).

Protein Storage

Protein is the body's source of "building block" material. So when you eat protein, if it is not needed for fuel (immediate energy), the body will use it to build up lean muscle tissue and other proteins.

Carbs Rarely Turn Into Fat

For all the reasons mentioned above, carbohydrates are rarely turned into fat stores. It's a myth that "carbs turn into fat". Carbs are almost always handled either by topping of glycogen stores or immediately used for energy needs as soon as it is digested.

If carbs are burned off or stored as glycogen, and protein is used to build muscle tissue, what remains? Fat (the fat you've eaten). When you eat excess calories, fat turns to fat. Not carbs.

When Are Carbs Turned Into Fat?

Carbs can only turn into fat under a specialized process called de novo lipogenesis. Studies show this only occurs in extreme circumstances in healthy people. What are those extreme circumstances? Two things would have to be true: 1) Eating in a calorie surplus (eating more overall calories than you burn) AND 2) Eating at least 700 - 900 grams of excess carbs per day over multiple days. A third requirement may also be necessary: a low-fat diet (less than 10% fat) because otherwise your body would store the fat instead of the carbs. To put these conditions in perspective, 700 grams of carbohydrate is equivalent to 3 1/2 cups of 100% pure sugar. Or the sugar in 28 Snickers bars! Can you eat that in a day? Probably not.

An exception might be people with severe insulin resistance, or hyperinsulinemia, or other metabolic syndrome related diseases. In those cases fat production can occur more readily with carb intake due to inefficiencies with metabolism, but such individuals shouldn't be eating very many carbs in the first place in order to control glucose and insulin levels. Another exception might be people who are very sedentary AND happen to eat a huge amount of carbs. In that case your muscles aren't using much glycogen stores, which means you're only using up glucose from the liver.

Even those exceptions rarely show themselves in scientific studies. Studies quite simply rarely if ever show carbs themselves turning into fat. Instead carbs are handled in another way and fat gains come from the dietary fat being consumed. However, one might say that in the end it doesn't really matter what turns to fat; what makes us fat is eating in excess of body's energy needs over a long period of time.

Body Weight Effects

Every gram of glucose stored in the body requires 3 grams of water, so when carb calories are stored as glycogen, most of it is just water! In contrast, because fat is so dense, it takes longer to accumulate in the body and affect weight. If you're being reasonably controlled in your diet, any body weight changes are most likely not changes in body fat. It's most likely Water Weight.

Alcohol Is Like a Toxin

Because alcohol cannot be stored in the body, your body is forced to burn it off. Metabolizing alcohol MUST be done before anything else or you'd get alcohol poisoning. Because people typically drink alcohol on top of everyday eating, it increases the chances of dietary fat being stored instead of burned off. You definitely want to avoid alcohol as much as possible on a weight loss plan.

Summary

If you overeat (calories in excess of body's needs), here's what happens to the macronutrients not used for immediate energy:

-

Carbs are stored as glycogen (rarely as fat).

Proteins are used to build stuff in the body.

Fat is stored in fat tissues.

If you undereat (calorie deficit) there is never fat storage no matter what kind of food you eat or what diet you're on. Even if you eat a diet of 100% carbs or a diet of 100% fat.

To re-emphasize the Energy Balance Equation -- decades of research has proven that it doesn't matter what type of food you are eating: high carb, low carb, high fat, high protein -- fat can only be gained if you are eating excess calories. If you are eating less calories than your body can use or get rid of (an energy deficit), then you will lose weight.

However, some nutrients are MUCH better diet foods. Some nutrients just make it easier to consume less calories. See Weight Loss Food Strategy.

©2025 LeanBodyInstitute.com. All Rights Reserved.