Metabolic Adjustments

You've probably seen the term "starvation mode", tossed around by the diet and fitness industry as being harmful and something to avoid. Other so-called diet gurus talk about how dieting or yo-yo-ing can damage your metabolism. Or that fasting or restricting calories causes permanent harm to your metabolism. They couldn't be more wrong.

Those are all myths or misunderstandings. (Or outright lies to make you afraid of actually taking actions that really make a difference.)

The word "starvation" is misleading. In research articles and studies, the term starvation or the "starvation response" is not what it sounds like. Researchers are not talking about death or dying.

A better phrase in our opinion, one that more accurately reflects what is happening is metabolic adjustments.

These adjustments aren't harmful and don't ruin your metabolism or stop you from losing weight. It happens to everybody when losing weight. No matter how you lose -- slowly, quickly, low-carb, low-fat, health food or junk food, yo-yo dieter or one-time dieter -- your body resists losing fat and reacts and adjusts accordingly. Unfortunately, there is no way to avoid metabolic adjustments if you want to lose weight.

The brain adjusts a huge number of systems in response to BOTH undereating and overeating, including metabolism, appetite, activity, energy, and hormones.

The simple fact is this: The ONLY way to avoid metabolic adjustments is to keep your weight exactly the same (avoid gaining, avoid losing).

The Energy Deficit Response

You can create an "energy deficit" and trigger metabolic adjustments by either reducing calories (going on a diet) or increasing physical activity -- or both. When you do this, your body senses you don't have enough calories to cover energy being expended. It also notices you are losing fat.

Your body is designed to stay in a narrow range for all systems -- it regulates them. This is sometimes referred to as homeostasis. For example, blood sugar levels, blood pressure, body temperature, oxygen levels. This includes fat levels.

Your body tries to correct this deficit in two ways:

-

You get hungry. This is your body telling you to increase energy intake ("Energy In")

By reducing number of calories you burn (energy expenditure, or "Energy Out")

The good news is that hunger is often short-lived and isn't typically a long-term problem when managed correctly. More on this elsewhere.

Response #2 is the Metabolic Adjustments which we'll talk about below.

Either way, your body resists weight loss. Why? From an evolutionary perspective, it's to slow how quickly you lose fat in order to ensure your survival as long as possible. Your body also wants to slow down energy expensive processes like protein synthesis, reproduction, and immune function. It's part of the reason why men tend to lose their sex drive (and ability) and women lose their period if they really "diet hard" or get really lean.

The second reason is to prime your body to put fat back on when calories become more plentiful again. It means you have to be extra cautious when transitioning from a diet.

Most people don't realize that our bodies resist weight gain, too. Unfortunately, the response is pretty weak. Yet it's one reason why everyone ends up feeling full at some point at meal: your body signals that you're done eating. That's why you gain fat over a relatively long period of time and not instantly.

However, your body is much more resistant to losing weight. Why? Most experts think it's for evolutionary reasons. Food wasn't as easy to get in the past, and starvation was a real possibility. The longer you kept your energy stores (fat), the longer your could survive. In the past, fat was an evolutionary advantage! There are relatively few people today who lose easily and have actually hard time gaining weight; again, evolutionary theory would say it's because so few of those body types survived in the past.

Let's talk more about response #2...

Metabolic Adjustment (Slowdown to "Energy Out")

The metabolic adjustment response consists of:

-

Normal weight-based adjustment

An extra adjustment, called the Adaptive Response

We're going to show you several graphs below to help illustrate metabolic adjustment visually. We think it helps, but if you have a hard time reading charts, don't worry, we'll also explain in the text.

These are examples only. The principles illustrated apply to everyone but your exact numbers will be unique to your situation. Also, in real life, weight loss doesn't happen in a straight line. Bottom line is that these charts are only for illustration purposes.

If you haven't already, you should first read about Resting Metabolic Rate and Energy Balance Equation ... or these charts won't make as much sense.

Metabolic Adjustments Due to Changes in Body Weight

The first kind of metabolic adjustment is based mainly on changes in your body weight.

You first have to understand the relationship between body weight and metabolic rate or Total Energy Expenditure. Basically, the more you weigh, the more calories your body burns. The less you weigh, the fewer calories. If you are a lot smaller than someone else, you generally cannot eat as many calories as they do, or else you will gain weight.

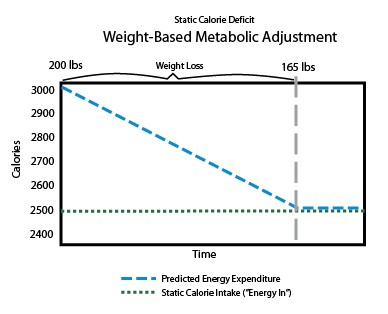

Take a look at the following graphs:

In this graph, we have an example female dieter who weighs 200 pounds. We're going to estimate she burns around 15 calories per pound (because she's moderately active and not sedentary). That means her maintenance calories or total energy expenditure (TEE) will be around 3000 calories per day.

She goes on a diet of 2500 calories, which is a 500 calorie reduction (deficit) below maintenance. That causes her to lose weight for some period of time. Her weight stops at 165 pounds because the calories she is taking in equal the calories her body is burning. There is no longer a deficit (the math: 165 lbs x 15 calories per pound = roughly 2500 calories).

Key point: Her new maintenance calorie level is 2500. If she wants to maintain her weight, she cannot go back to eating 3000 calories a day because her body is now smaller. She is now at the same calorie level as someone else who has never dieted and always weight 165 pounds: both persons can only eat roughly 2500 calories to maintain. (Note however, that the Adaptive response described below may change this)

What has happened is that your body has adapted to your new weight and it's totally normal. At this point it's easy to think "I can hardly eat anything", or "my body is holding on to fat and my metabolism is shot", but in reality you only think this because you are comparing it to what you used to eat. Your body is smaller so you cannot eat the same amount as before -- and (another key point) you have to drop calories even further if you want to start losing again.

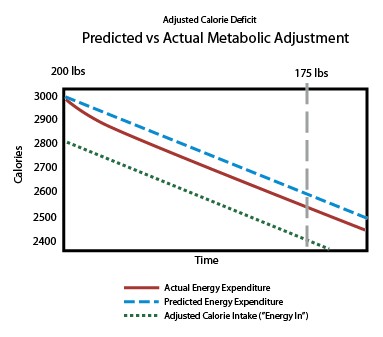

In the this graph, this dieter is also on a calorie deficit (eating less than her body burns); however she dynamically adjusts calories according to her changing weight. As she loses, she calculates her new TEE and subtracts 200 calories. (In practice, that's a rather small deficit and can be hard to do by calorie counting alone; it's just an example). So she gradually is eating less, but in proportion to her weight.

In theory -- like the chart shows -- she could keep losing until her ideal weight is met.

However, there is another factor involved...

The Adaptive Response

Some people have extra resistance or extra adaptation beyond what would be expected for their body weight. This can be referred to as the Adaptive Metabolic Adjustment, Adaptive Thermogenesis, or simply the Adaptive Response. It's a reduction in TEE (total energy expenditure). Essentially, the body is making extra adaptations to preserve fat stores.

This undesirable response is highly variable from person to person. If/when it occurs, a number of studies show it is in the range of 200 - 500 calories per day, or perhaps around 10% - 25% lower energy expenditure than someone of the same size who has always weight the same. But exact figures aren't truly known.

This happens for two reasons:

1) Spontaneous reduction in physical activity

Surprisingly, research indicates that most -- or even all -- of the Adaptive Response is due to a reduction in NEAT. That's an acronym for "Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis", the unconscious, natural movement you do outside of formal exercise as you go about your day. Stated another way: you simply move less and don't realize it. Your body also becomes more efficient, so you actually expend less energy when moving around. Inferring from studies, this may account for around 85 - 100% of the Adaptive Response.

2) Reduction in normal RMR

Research is split on this topic. About half of the research shows that RMR decreases below normal in response to weight loss. Half of the studies don't show it. When it occurs, it means your tissue burn fewer calories per unit mass than before. This response is greatest during active weight loss; that is, while you are on a diet and losing, after which it increases and may return to normal. Other studies show it persists long-term. How much can RMR drop? Studies indicate that the obese who have dieted down only have a 1-5% reduced metabolism, at the most. Leaner individuals who are below "average" fat levels (such as athletes) and who diet down to super low levels may see up to a 15% reduction particularly during dieting itself. Some experts believe that for those trying to reach the lowest fat levels, you can avoid the Adaptive response by losing weight very gradually. For the obese or overweight, the rate of weight loss hasn't been proven to be a factor.

How does the Adaptive Response affect weight loss?

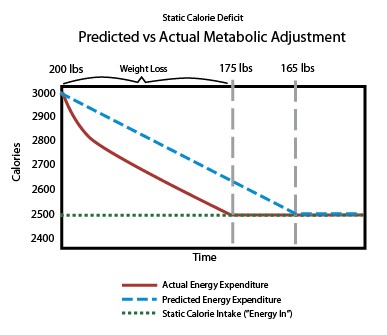

Take a look at the following charts.

Note we are looking at the same example dieter as in the previous examples, using the same two diet approaches.

In this graph, as before, she goes on a diet of 2500 calories, which is a 500 calorie reduction (deficit) below maintenance. That causes her to lose weight for some period of time.

The dotted blue line still shows how her TEE goes down with weight loss: that's what we predict will happen. See the red line? That's the Adaptive response at work. Instead of burning 15 calories per pound, her body is only burning closer to 14 calories per pound because her body "slows down" and reduces energy expenditure -- it tries to become more energy efficient. That means her total TEE will equal her 2500 calorie diet earlier; for example, perhaps when she is only 175 pounds instead of 165. The math: 175 x 14 = 2450 (or roughly 2500). Basically, she stops losing 10 pounds earlier than would be expected.

In the this graph, as before, she dynamically adjusts calories according to her changing weight.

The adaptive response occurs in this situation as well. The red line shows her energy expenditure (TEE) is actually less than it "ought" to be.

However, notice that with a dynamic or adjusted calorie deficit like the chart shows, the red line can never "catch up" with the green line. The energy balance principle promises that if you are constantly adjusting calories lower to account for your reduced weight, then weight loss never stops even if the body tries to adapt (e.g., in spite of the Adaptive Reponse).

Note that a small deficit of 200 calories (a rather "easy" diet) means the Adaptive Response won't be quite as strong, but it still slows weight loss because it reduces the expected calorie deficit (for example, what is supposed to be a 200 calorie deficit is now more like 150-175).

Even though weight loss never stops if calories are adjusted for body weight, there are some unusual circumstances where weight loss appears to stop when it really hasn't (more on that in other pages - see Water Weight Fluctuations). And there are times that the body fights back hard enough that you'll see more success by taking a break from calorie reduction (see Normalizing the System below, and Diet Vacation / Take Breaks). It's still true that if calories are below energy expenditure, you will still be losing, but it could slow to a crawl.

The main thing to remember is that this Adaptive component exists, and can help explain why weight loss is slower, slows down or even stops earlier than expected.

Is The Adaptive Response Permanent?

That's a valid question -- because when people talk about damaged metabolisms, this is typically what they're referring to.

Remember, there is no such thing as real damage. The Adaptive response if/when it happens is normal -- and does not permanently "ruin" your metabolism. You body's adaptive response is not the fault of dieting or weight loss itself -- to avoid it you would have had to avoid becoming overweight in the first place.

The bad news is that a lot of research indicates that metabolic adaptations can remain for years, and it is unknown if it ever goes back.

The good news?

First, it varies from person to person. It may not even affect you, or not enough to notice.

Second, you can do things to completely counteract it. You may recall that the greatest contributor is a reduction in NEAT, which you can deliberately compensate for. You can consciously increase your activity. Regular exercise is the #1 way to keep the weight off.

Third, there are still unanswered questions about the adaptive response and its affect on weight maintenance. It's not an area of absolute science.

The only thing that is commonly agreed upon is that it is "likely" (but not guaranteed) that a formerly obese or very overweight person will have to work harder to keep the weight off than a person who has never had a weight problem. That fact is commonly explained by (blamed on) the Adaptive Response -- but it may not be that simple. Especially when NEAT is shown to be one of the greatest factors. When you factor in individual behavior, individual habits and our food environment, it starts to get really difficult to pin down the real reason for weight regain.

In the end it may not really matter. Regardless of genes or adaptive responses, you still follow the same tactics and techniques for weight control -- and they are reasonable and doable!

Even if your body adapts to the worst possible degree (say, 400-600 calories per day at most) you still absolutely can do things to counteract it. It won't ruin your chances of maintaining long term.

There are plenty of examples of people who were once obese -- in fact they may even have been obese as a child and struggled their whole life -- who end up losing weight and keeping it off (see Genetics and Set Points).

And no matter what, everyone who loses weight has to stay watchful and maintain certain habits to keep the weight from creeping back, regardless of the Adaptive response. One mindset successful maintainers have is to basically treat weight maintenance like a part-time job -- one of the best, if not THE best part-time jobs you could ever undertake. We're talking about your health and your life here!

All the techniques on this site can be used to help you out. Everything adds up.

Normalizing the System (Stabilization)

So you have now seen how the body can resist or fight back and lower metabolism beyond where it would normally be, and alter hormones outside of a normal state. This is a "down-regulated" state.

It means your body COULD be burning more (you could be eating more!) and still remain at the same weight ... if you could correct your metabolism, or "up-regulate" it. In this state, it's also harder to lose weight even if you continually lower calories.

In effect, it's an abnormal -- or unbalanced -- situation.

There are various solutions for this. Essentially it involves eating more calories including carbohydrates. See Diet Vacations / Take Breaks.

Here is a chart that shows a "corrected" metabolism:

Here is the same dieter, on a 500-calorie per day deficit. Again, we show the same predicted TEE (dotted blue line) and the actual TEE (red line). But when she's reached a plateau, she increases calories slightly. The chart shows 100 calories per day, but it could actually be more -- there are certain strategies for this (what to eat, how much to eat). The red line (TEE) goes up, gradually reaching more normal levels, and equaling calorie intake.

The basic concept is that when you eat more (carbs, in particular) it makes your body happy. It starts up-regulating everything. Your energy expenditure increases. Your weight should stay the same or roughly the same, yet you are eating more. Your weight is stabilizing; your body is aiming for homeostasis again.

More Details: Why Does Body Resist and What Happens?

The first reason the body resists is to slow how quickly you lose fat in order to ensure your survival as long as possible. Your body also wants to slow down "energy expensive" processes like protein synthesis, reproduction, and immune function. It's part of the reason why men tend to lose their sex drive (and ability) and women lose their period if they really "diet hard" or get really lean.

The second reason is to prime your body to put fat back on when calories become more plentiful again. It means you have to be extra cautious when transitioning from a diet.

How does the body "fight back", and how does it cause a reduction in energy expenditure?

Here are the main factors:

-

Decrease in physical activity

Appetite/hunger increases

Hormonal changes in regulation

Extra Adaptations:

-

Lowered resting metabolism (RMR)

Fat burning more difficult

Some of those factors overlap; some are involved in both "normal" responses and the extra Adaptive component. But the most resistance and undesirable changes are the Adaptive components.

Those changes occur most strongly during active dieting (while you are in a calorie deficit). They linger after dieting too, but as you increase calories (reverse diet) it gradually goes away as explained above.

Decrease in Physical Activity

This mostly affects NEAT (non-exercise activity thermogenesis) -- those spontaneous, mostly unconscious movements you make. You don't really have control over this, but it can significantly reduce energy expenditure by as much as 200 - 900 calories per day or so. It's a very individualized response. Also, you probably don't want to exercise quite as much. Even when you exercise you will end up wanting to sit down more during the rest of the day than normal, often without realizing it.

Appetite Increases

If you don't "give in" to increased hunger, then this shouldn't affect weight loss by itself. But it does make it harder and may unconsciously influence your judgment in small ways even if hunger isn't that great. Mostly, however, this signal telling you to eat more affects you AFTER your diet, during the transition to maintenance. Again, this goes back to the old "starvation" idea. Sure, your body wants you to eat to get back to the fat levels you had previously -- but with some patience, those hunger hormones will back off and stabilize.

Lowered RMR

Some studies show that during active dieting, your tissues actually burn fewer calories per unit mass -- in essence, your metabolism slows. Other studies -- in fact about half of them -- don't show this adaptation at all.

Fat Burning More Difficult

In general, during metabolic adaptation, your body makes fat mobilization and burning more difficult, and fat gain easier. This another reason why it's easy to gain after your lose weight. As soon as calories come in, your body wants to store them for the future. There's nothing "wrong" with this -- you just have to take care and be patient.

Hormonal Changes

Your body weight is regulated or internally controlled by a feedback loop between certain hormones, and your hypothalamus in your brain. The hormones that "tell" the hypothalamus about bodyfat level, and how much you're eating include leptin, insulin, ghrelin, peptide YY, among others. Thyroid levels can also drop, which can slow weight loss. Cortisol levels also increase, which can mask weight loss. Other affected hormones include testosterone, estrogen and progesterone. This is part of why dieting tends to affect the menstrual cycle and why men who get extremely lean can have problems with libido or sexual function.

©2025 LeanBodyInstitute.com. All Rights Reserved.